Writing a Basic App in Redux

This article is outdated and has since been updated to 2018 technologies in davidandsuzi.com/writing-a-basic-react-redux-app-in-2018

I’ve been a bit heads down for the last two months, working on a project with React 0.12.2 and Reflux. In that course of time, the React ecosystem has begun to feel foreign to me. React is up to 0.14 beta, React-Router is up to 1.0 beta, a few ES6 and ES7 patterns have been popularized, and Redux has gained a large amount of support and momentum and arguably emerged as the Flux library of choice.

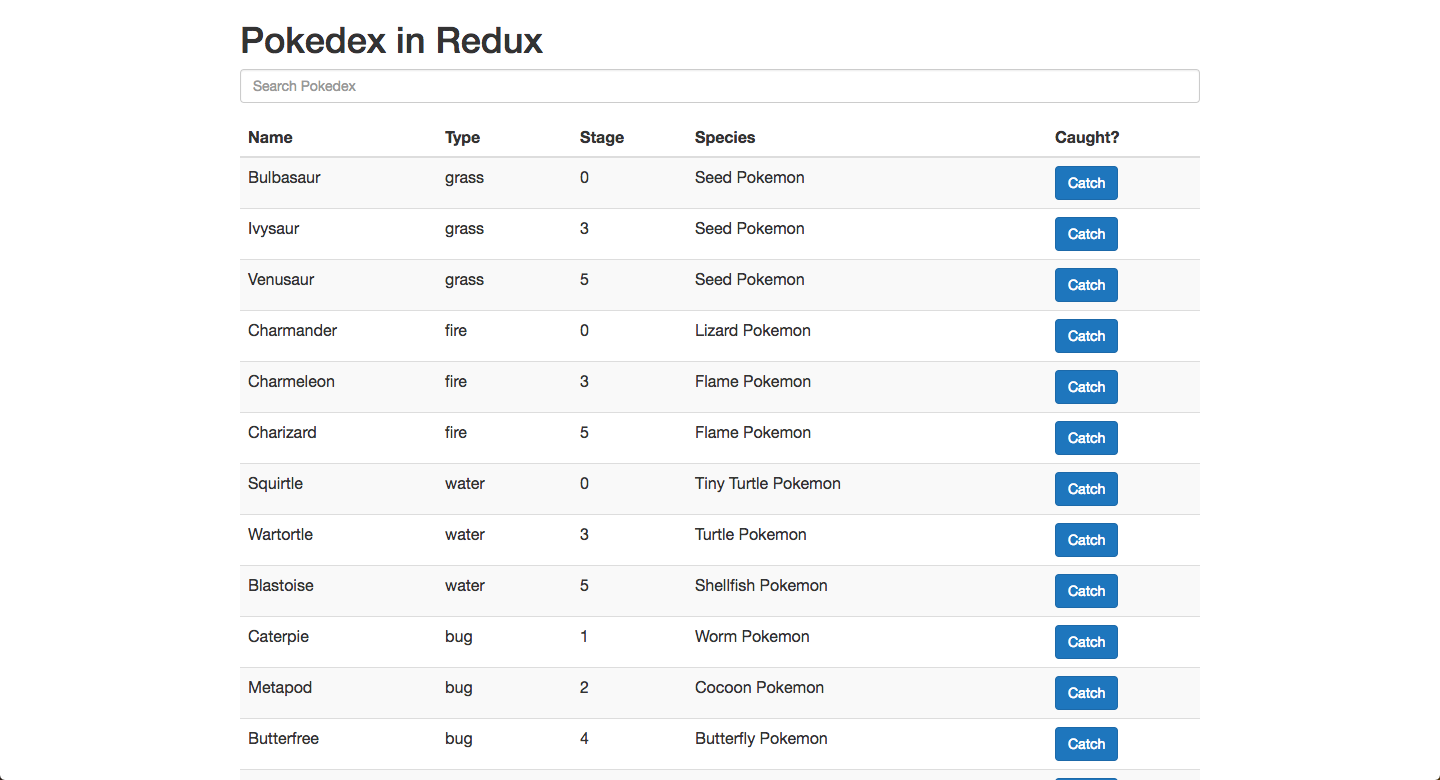

I’ve been wanting to look at Redux for a while, but the only way I can motivate myself to learn stuff like this is by doing write ups. So let’s build a simple Pokedex app that displays a list of Pokemon, has a search input field, and lets you click a button to catch some Pokemon. That’s it, intentionally contrived. Everything will be synchronous for now, but I’d ambitiously like to do writeups in the future that introduce the capabilities/usage of Redux Dev Tools, ImmutableJS, GraphQL, and server-side rendering.

[This article is being written specifically for those who have prior experience with React and Flux, but have not had any prior experience with Redux.]

Demo was at http://davidchang.github.io/redux-pokedex/](http://davidchang.github.io/redux-pokedex/), but is now no longer available

Code: https://github.com/davidchang/redux-pokedex

Screenshot:

Starting

To start, I’ll clone the TodoMVC example in Redux:

git clone https://github.com/gaearon/redux.git

cd redux/examples/todomvc

npm install

npm start

open http://localhost:3000

That provides us with a webpack-dev-server that transpiles JS with Babel and hot reloads. This is a pretty solid boilerplate for any app.

I copied a list of the original 151 Pokemon from here and started working on the store first, since that is the biggest difference about Redux - a stateless store whose action handlers are pure functions.

Stores

My initial state will look something like this:

const initialStore = {

pokemon : PokemonList,

searchTerm : ‘',

caughtPokemon : [],

};

searchTerm, here, represents an input field where we can narrow down the list of Pokemon. Let’s write the actionHandler that corresponds to whenever the SEARCH_INPUT_CHANGED action is fired. When that happens, we’ll want to respond with a new object that updates searchTerm and the list of pokemon to display. In a traditional Flux store, we’d just mutate an internal state:

export default function pokemon(state = initialState, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case SEARCH_INPUT_CHANGED:

this.searchTerm = action.searchTerm;

this.pokemon = someFilteringMethod();

this.trigger();

default:

return state;

}

}

but since stores need to be stateless in Redux, we need to think differently (more functionally) and make sure to create a new state object upon every action instead of modifying the previous state object:

export default function pokemon(state = initialState, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case SEARCH_INPUT_CHANGED:

return {

...state,

searchTerm : action.searchTerm,

pokemon : someFilteringMethod()

};

default:

return state;

}

}

This sort of object manipulation is not how I normally think in JavaScript, which is an argument to me to consider using ImmutableJS, since that would also have the same sort of overhead in needing to learn a new API. Look for that in a future writeup.

Action Creators

Let’s talk about the action creator that will trigger the action handler we just wrote. The whole thing looks like this:

export function searchTermChanged(searchTerm) {

return {

type: types.SEARCH_INPUT_CHANGED,

searchTerm

};

}

Pretty straightforward, though note that it’s using an ES6 object shorthand property to pass the searchTerm parameter as the value of the searchTerm key. This action creator will get invoked by the view - specifically, by the onChange handler on an input field. You’ll notice that all this does is return an object and it does not actually dispatch anything - we will discuss how the interaction occurs in this next section.

Views

The last piece of the puzzle is the view and how it receives data from the store, which was the area of biggest confusion for me. If you’re looking at the TodoMVC example code, you’ll see two JS files under the containers directory - an App.js, which is the root component of your app, and a component specific to your application (here, PokedexApp).

App.js looks like this:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import PokedexApp from './PokedexApp';

import { createRedux } from 'redux';

import { Provider } from 'redux/react';

import * as stores from '../stores';

const redux = createRedux(stores);

export default class App extends Component {

render() {

return (

<Provider redux={redux}>

{() => <PokedexApp />}

</Provider>

);

}

}

The Provider is used to expose the Redux instance (the result of createRedux(stores)) on the context, where it can be accessed from any of its children. The Redux instance is the glue that enables the connection of the dispatcher to stores and manages the state of the stores (since stores are stateless, pure functions).

The line {() => <PokedexApp />} declares a function that is passed to Provider as props.children and is invoked in the Provider’s render function. I have no idea why this is written this way or if it is necessary to be written this way, but this same sort of pattern is used again in the Connector component in PokedexApp. PokedexApp looks like this:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import { bindActionCreators } from 'redux';

import { Connector } from 'redux/react';

import MainSection from '../components/MainSection';

import * as PokemonActions from '../actions/PokemonActions';

export default class PokedexApp extends Component {

render() {

return (

<Connector select={state => ({ pokemonStore : state.pokemon })}>

{this.renderChild}

</Connector>

);

}

renderChild({ pokemonStore, dispatch }) {

const actions = bindActionCreators(PokemonActions, dispatch);

return (

<div>

<MainSection data={pokemonStore} actions={actions} />

</div>

);

}

}

There are two new concepts here - Connector and bindActionCreators.

The Connector component uses the Redux instance that we set earlier in our context in the parent component. It ties the entire flow between actions and stores together. This happens in two ways - first, changes in the state of the store automatically propagate down to the view and second, views receive access to a dispatch function that can communicate to the stores.

As for the store’s state propagating into the view, the Connector component takes a select prop to be a function that takes in the store’s current state and returns some subset or slice of that data, which will be passed down to that renderChild child along with a dispatch method.

As for views receiving a dispatch function, that brings us to bindActionCreators. Since an action creator just returns an action object to be dispatched (but doesn’t actually dispatch the action object itself), it needs access to our app’s specific dispatch function which can communicate with our stores. bindActionCreators does this, accepting our action creators as the first parameter and the scoped dispatch function as the second.

If you look at example code, you’ll realize that these bound action creators are propagated down to the rest of the app through props - this happens because these action creators need to be specifically bound to a dispatch function that is specifically bound to our stores. (The dispatch function is bound to our stores when we create our Redux instance in the root App.js component.)

Now, the rest of our view is just a normal React app. Our store data and actions will be propagated down from our single PokedexApp component and consumed accordingly.

That’s actually all there really is to Redux. There are plenty of other concepts and verbiage surrounding Redux, like higher order functions and customizing the dispatcher through middleware, but this is meant to be an introductory tutorial, so we’ll tackle those topics and features at a later point.

[To finish our Pokedex app, we also need to add the ability to mark a Pokemon as caught. To do this, I added a MARK_CAUGHT constant, wrote an action handler called markCaught that returned an object with type MARK_CAUGHT, and wrote code to handle the MARK_CAUGHT type in my store.]

Closing

Overall, my experience with Redux has been unsurprisingly positive and I’m eager to explore the tooling around it. As much as we all agreed that React components should eliminate side effects and be pure functions, it’s a bit convicting that we then proceeded to write many Flux implementations with side effects and stateful stores. Dan Abramov and the rest of the Redux contributors offer a refreshing departure from the current Flux landscape and help get us back on the right track.